|

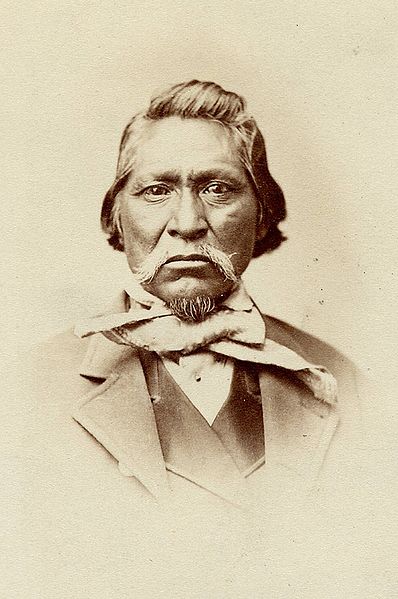

Kanosh (1812?-1884) was the leader of the Pahvant Utes from the 1850s until the time of his death. According to Mormon records he was the son of Kashe Bats and Wah Goots. The Pahvant band ranged the deserts surrounding Sevier Lake. With the intrusion of whites into this area, Kanosh struggled to insure the hegemony and survival of his people through negotiation rather than conflict. It was a strategy which proved as futile as the other, however.

Kanosh's efforts at conciliation were early manifest in his turning over to military authorities six Pahvants supposedly involved in the killing of U.S. surveyor Captain John Gunnison and other members of his survey party in 1853. These six were probably only peripherally involved and were surrendered merely to satisfy federal investigators. The Mormon jurors at the trial in Nephi City found three guilty of manslaughter and acquitted the others. Federal officials were convinced that Mormon officials had staged the trial to mollify non-Mormon opinion and to protect Kanosh's favored Indian group.

Kanosh had taken over leadership of the Pahvant group from Chuick, a leader more eager to fight the invading Mormon settlers. Perhaps Kanosh's willingness to work with non-Utes came out of his experiences working in the missions of California. Whether that work was voluntary or part of the long-standing slave trade of Indians into the Spanish settlements is not known. Certainly, the physical characteristics of Kanosh and others of the "Bearded Utes," as Escalante had called the Pahvants in the 1770s, suggest generations of contact with the Spaniards. Kanosh spoke Spanish and seems to have had a facility for languages, as he also easily picked up English.

Kanosh represented the Pahvant Utes at the signing of the treaty with Brigham Young which signalled the end of the Walker War in 1854. A year later, federal Indian Agent Garland Hurt established four Indian farms, including one at Corn Creek where Kanosh's band had a major camp. (Pahvants with other leaders camped at Sevier Lake.) Kanosh and several other Pahvant families took up farming. In 1858 Kanosh was baptized a Mormon and he occasionally preached from Mormon pulpits, including the following: "I wish to do right and have my people do right. I do not want them to steal nor kill. I want to plant and raise wheat and learn to plow. . . . I want to learn to read and write and have my children learn."

Even after the Indian farm was abandoned by federal officials, the Pahvants at Corn Creek continued to farm. Surrounding Mormon settlers gave them some assistance. And although Kanosh was involved in the negotiations of the 1865 Spanish Fork treaty in which Utes agreed to move to the Uinta Basin, Kanosh and his group continued at Corn Creek until a grasshopper invasion in 1868 destroyed most of their crops. However, Kanosh and his people did not always remain in the Uinta Basin; they returned often to Corn Creek to farm, forage, and beg from Mormon settlers.

In 1872 hundreds of Utes including Kanosh and his followers gathered in the Sanpete area. Kanosh also attended a council at Springville and joined in the complaints to federal officials and Mormon Church leaders about conditions at the Uinta reservation. That fall federal officials sent a group of Ute leaders to Washington, D.C., to negotiation peace and further land cessions in Colorado. Kanosh went and promised President U.S. Grant to remain on the reservation in return for supplies and stock. During that trip John Wesley Powell described Kanosh as a man of "ability" and "influence."

Mention should be made of Kanosh's four wives since he is as much known through stories about them as about himself. One of his wives killed another and was punished by Kanosh by being buried alive. Another of his wives, Sally, was a Ute woman who had been raised in Brigham Young's household.

Conditions on the reservation remained grim, and Kanosh continued to use the Corn Creek area. Most of his followers had also been baptized as Mormons; however, their numbers dwindled from disease, inability to master a changed environment, and economic dependency. Kanosh's survival strategy of conciliation and accommodation thus also ended in the Indians' loss of land and culture.

|